Jane Boroski, seven months pregnant and thirsty after spending hours in the summer heat at the county fair near Swanzey, New Hampshire, stopped at a convenience store on her way home to pick up a can of soda after a long day that would soon become the worst night of her life.

It was a hot, humid summer 35 years ago this month, and Boroski pulled over in an empty parking lot to slip some pocket change into a vending machine outside a convenience store that had closed for the night.

“I was 22 years old, I was seven months pregnant, and I was stabbed 27 times by the Connecticut River Valley serial killer,” Boroski, who survived the attack along with her then-unborn child, told Fox News Digital.

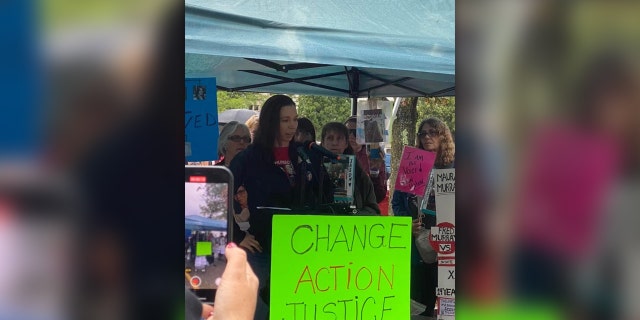

Jane Boroski, center, was 22 years old and seven months pregnant with her daughter, left, in 1988 when a man believed to be the Connecticut River Valley serial killer stabbed her 27 times in a dark New Hampshire parking lot. (Jane Boroski)

Swanzey is a small town near the borders with both Massachusetts and Vermont. Boroski said there was virtually no crime at the time and that she had no reason to worry when a strange man pulled up next to her in the dark parking lot.

She left the car door unlocked, opened her soda and took a sip. The stranger knocked on her window and asked if the payphone was working.

“Then he opened my door and tried to take me out of the car,” she said. “And I was determined I wasn’t going to go with him – so we fought quite a bit in my car.”

“Me and my daughter, we’re survivors, and that’s something he couldn’t take away from me. I survived whatever evil thing he tried to do.”

In the scuffle, she leaned back and tried to kick him – missing her target but shattering her own windshield.

“Then he took a knife out and said, ‘Maybe this will persuade you to get out of the vehicle,’” she recalled. “So, I did. I got out of the car.”

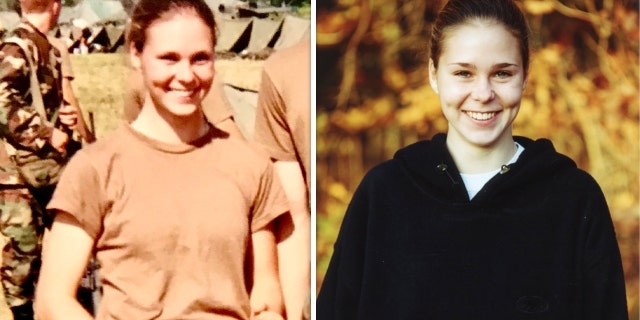

The Connecticut River Valley serial killer targeted women across New England states. Victim Lynda Moore, 36, left, was home alone on April 15, 1986, when someone entered her house and killed her, according to Vermont State Police. Another victim, Barbara Agnew, 39, right, was found dead 12 miles away from where police found her car parked at a rest area at White River Junction. (Vermont State Police)

Even then, the situation began to calm down, she said. He asked her “weird questions” and accused her of beating up his girlfriend. He wanted to know if she had Massachusetts license plates. She didn’t – she was from New Hampshire.

“I got really confused, but I kind of put my guard down because I wasn’t scared anymore,” she said. “I thought maybe he just confused me with somebody else.”

The stranger had backed off, put the knife away and was walking toward his own car.

Julie Murray, sister of missing nursing student Maura Murray, speaks at a rally for cold-case victims and their families on Aug. 15, 2023, in Concord, New Hampshire. (Nancy Cory)

“Oh my God, he’s leaving,” she thought at the time, Boroski said. “And I got a smashed windshield. So, I was like, ‘So, what about my windshield?’ And those are the words I will forever regret for the rest of my life.”

He took the knife out again. She saw headlights on the rural road and ran toward them, screaming for help. He tackled her like a football player, stabbed her 27 times and escaped into the night. She woke up in a hospital bed, fought through her injuries and saw on news reports that police believed she had been attacked by an active serial killer in the region – and that she appeared to be his only survivor.

“That brought on a whole new layer of terror,” she said. Her attacker hadn’t been caught. Her name and face were broadcast all over TV. What if he came back to finish the job?

But he never did, and she may have been his final victim as well. But he hasn’t been captured either. So, Boroski, now 57, and the families of other cold-case victims teamed up to march on the state capital, asking for help from Attorney General John Formella’s office, the state’s lead investigative agency.

Boroski now has a podcast called “Invisible Tears” and is actively advocating for justice for her fellow Connecticut River Valley victims and the families in other unsolved cases across the state.

She says the “monsters” behind these crimes need to be taken off the street and that survivors deserve answers, even if they can’t find closure. And she finds hope each time a case is solved – including the recent arrest of a suspected Long Island serial killer last month and two arrests in decades-old cases in her home state of New Hampshire this year.

“I have a granddaughter, from my daughter – I’m very blessed to have her and my daughter,” Boroski said. “Me and my daughter, we’re survivors, and that’s something he couldn’t take away from me. I survived whatever evil thing he tried to do.”

Images provided by MauraMurrayMissing.org show her at a West Point fitness event in 2000 and in another undated portrait. (MauraMurrayMissing.org)

Through her efforts, she met Julie Murray, the sister of nursing student Maura Murray, who vanished after a single-car crash 19 years ago, at a vigil, and the two bonded. Together, they helped organize a recent march on the state capital calling for justice for cold-case murder victims and the families of people whose loved ones have vanished in unsolved disappearances.

Murray’s family has been advocating for justice for nearly two decades, hiring private investigators and offering to pay for state-of-the-art lab testing out of pocket, but they havel been frustrated by a lack of answers in Maura’s case.

“I feel so supported by the other families – I feel so empowered,” Murray told Fox News Digital. “I haven’t felt this way because normally when you’re a family with a real life tragedy, you’re kind of siloed … but after talking to all these family members, and they’re sharing the same grievances, I’m like, ‘I’m not alone in this.'”

“I’m hoping that the attorney general’s office realizes that you’ve got a whole bunch of families that are raring to go, and this march was just step one,” Murray said.

Following the march, state officials have begun setting up one-on-one meetings with mourning families to update them on their cases and hear out their grievances, leaving the advocates with a feeling of acknowledgment they say that haven’t received in recent years.

“There has been no correspondence between investigators and family, which was the driving force for us to hold the rally,” said Chloe French, another march organizer and a friend of Trish Haynes, who was found dead and dismembered in a pond in 2018. “Following the march, we were granted a sit-down meeting with the AG, chief of homicide and the director of the victims’ advocacy program, which is to be held on Sept. 1.”

New Hampshire’s Trish Haynes was found in 2018 more than a year after she went missing in a remote pond, dead of an apparent homicide. No suspects have been arrested. (Family of Trish Haynes)

Haynes had been missing for more than a year when she was found dead in an apparent homicide in a remote pond in Grafton. Although friends believe they may have a potential suspect in mind, no one has been arrested.

State officials have voiced support for the victims’ families and vowed to crack the cold cases – noting that several have been solved in recent years and that the technology that helps detectives do so is improving.

“We are optimistic that the hard work carried out daily by the dedicated public servants who make up our homicide and cold-case units might provide victims some hope,” Mike Garrity, a spokesperson for Formella’s office, told Fox News Digital.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

New Hampshire police solved 92.3% of last year’s homicides, he said, which is well above the national clearance rate of 54.3%. And the state is continuing to invest in improving its ability to hunt down people who think they’ve gotten away with murder.

“Moving forward, we are continuing to expand our efforts and increase the resources dedicated to solving cold cases,” he said. “This month an experienced cold case investigator from Maricopa County, Arizona, joined the cold case unit and state police are using a $1.5 million grant to invest in DNA testing improvements now being implemented at the state’s forensic lab.”

Formella’s office is also prosecuting Adam Montgomery, the Manchester felon charged with beating his 5-year-old daughter, Harmony, to death and hiding her remains after convincing a court to grant him custody following his release from prison on a robbery conviction.

Tips can be shared with the New Hampshire Cold Case Unit at 603-223-3648 or coldcaseunit@dos.nh.gov.