CNN

—

German food is rich, hearty and diverse. It’s comfort eating with high-quality, often locally sourced ingredients.

The cuisine of Germany has been shaped not only by the country’s agricultural traditions but by the many immigrants that have made the country home over the centuries.

It’s definitely more than a mere mix of beer, sauerkraut and sausage.

Today Germans appreciate well-prepared, well-served meals as much as they do a quick bite on the go. This is a country of food markets, beer gardens, wine festivals, food museums and high-end restaurants.

So: Haben sie hunger? Are you hungry now? Check out our list of 20 traditional German dishes that you need to try when you travel there.

Named after the former East Prussian capital of Königsberg (now Kaliningrad in Russia), this tasty dish of meatballs in a creamy white sauce with capers is beloved by grandmothers and chefs alike.

The meatballs are traditionally made with minced veal, onion, eggs, anchovies, pepper and other spices. The sauce’s capers and lemon juice give this filling comfort food a surprisingly elegant finish.

In the German Democratic Republic, officials renamed the dish kochklopse (boiled meatballs) to avoid any reference to its namesake, which had been annexed by the Soviet Union. Today it’s possible to find königsberger klopse under their traditional name in most German restaurants, but they are especially popular in Berlin and Brandenburg.

Maultaschen from Swabia, southwestern Germany, are a lot like ravioli but bigger. They are typically palm-sized, square pockets of dough with fillings that run the gamut from savory to sweet and meaty to vegetarian.

A traditional combination is minced meat, bread crumbs, onions and spinach – all seasoned with salt, pepper and parsley. They’re often simmered and served with broth instead of sauce for a tender, creamier treat, but are sometimes pan-fried and buttered for extra richness.

Today you can find maultaschen all over Germany (even frozen in supermarkets) but they’re most common in the south.

Here the delicious dumplings have become so important that in 2009, the European Union recognized Maultaschen as a regional specialty and marked the dish as significant to the cultural heritage of the state of Baden-Württemberg.

Labskaus is not the most visually appealing dish, but a delectable mess that represents the seafaring traditions of northern Germany like no other. In the 18th and 19th centuries, ship provisions were mostly preserved fare, and the pink slop of labskaus was a delicious way of preparing them.

Salted beef, onions, potatoes and pickled beetroot are all mashed up like porridge and served with pickled gherkins and rollmops (see below). It has long been a favorite of Baltic and North Sea sailors.

Today the dish is served all over northern Germany, but especially in Bremen, Kiel and Hamburg. And while on modern ships fridges have been installed, it remains popular as a hangover cure.

There is no Germany without sausages.

There are countless cured, smoked and other varieties available across wurst-loving Germany, so, for this list we will focus on some of the best German street food: bratwurst, or fried sausages.

There are more than 40 varieties of German bratwurst. Fried on a barbecue or in the pan, and then served in a white bread roll with mustard on the go, or with potato salad or sauerkraut as the perfect accompaniment for German beer.

Some of the most common bratwurst are:

– Fränkische bratwurst from Fraconia with marjoram as a characteristic ingredient.

– Nürnberger rostbratwurst that is small in size and mostly comes from the grill.

– Thüringer rostbratwurst from Thuringia, which is quite spicy. Thuringia is also the home of the first German bratwurst museum, which opened in 2006.

The most popular incarnation of bratwurst, however, is the next item on our list.

Practically synonymous with German cuisine since 1945, currywurst is commonly attributed to Herta Heuwer, a Berlin woman who in 1949 managed to obtain ketchup and curry powder from British soldiers, mixed them up and served the result over grilled sausage, instantly creating a German street food classic.

Today boiled and fried sausages are used, and currywurst remains one of the most popular sausage-based street foods in Germany, especially in Berlin, Cologne and the Rhine-Ruhr, where it’s usually served with chips and ketchup or mayonnaise or a bread roll.

Not the most sophisticated of dishes, but a filling street snack born out of necessity about which all of Germany is still mad: some 800 million are consumed a year.

Döner kebab was introduced to Germany by Turkish immigrant workers coming here in the 1960s and ’70s. One of the earliest street sellers was Kadir Nurman, who started offering döner kebab sandwiches at West Berlin’s Zoo Station in 1972, from the where the dish first took both West and East Berlin by storm and then the rest of Germany.

From its humble Berlin beginnings when a döner kebab only contained meat, onions and a bit of salad, it developed into a dish with abundant salad, vegetables (sometimes grilled), and a selection of sauces from which to choose.

Veal and chicken spits are widely used as is the ever-popular lamb, while vegetarian and vegan versions are becoming increasingly common.

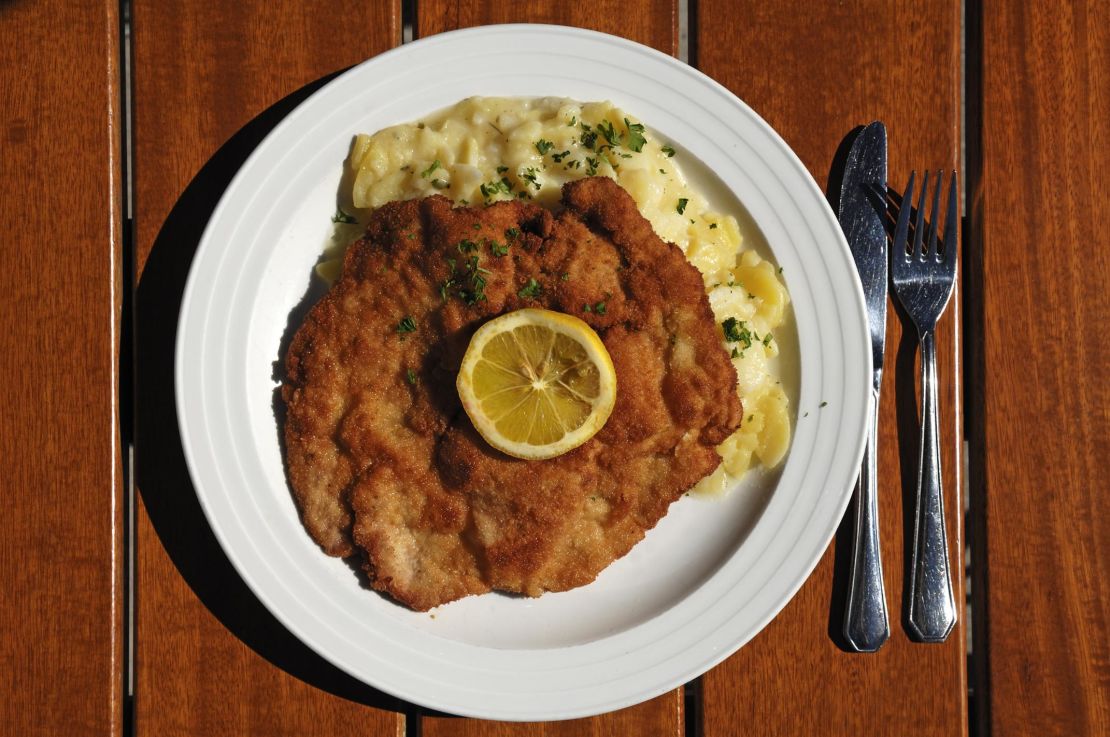

Some might argue that schnitzel is Austrian and not German, but its origins are actually Italian.

This controversy hasn’t stopped the breaded and fried meat cutlets to become popular everywhere in Germany, however. While the Austrian or Vienna schnitzel is by law only made with veal, the German version is made with tenderized pork or turkey and has become a staple of most traditional restaurants.

Whereas Vienna schnitzel is served plain, Germans love to ladle a variety of sauces over their schnitzel. Jägerschnitzel comes with mushroom sauce, zigeunerschnitzel with bell pepper sauce and rahmschnitzel is served with a creamy sauce.

All go well with fried potatoes and cold lager or a Franconian apple wine.

Spätzle originally come from Baden-Württemberg. Essentially a sort of pasta, the noodles are a simple combination of eggs, flour, salt and often a splash of fizzy water to fluff up the dough. Traditionally served as a side to meat dishes or dropped into soups, it can be spiced up by adding cheese: the käsespätzle variant is an extremely popular dish in southern Germany, especially Swabia, Bavaria and the Allgäu region.

Hot spätzle and grated granular cheese are layered alternately and are finally decorated with fried onions. After adding each layer, the käsespätzle will be put into the oven to avoid cooling off and to ensure melting of cheese. Käsespätzle is a popular menu item in beer gardens in summer and cozy Munich pubs in winter.

Rouladen is a delicious blend of bacon, onions, mustard and pickles wrapped together in sliced beef or veal. Vegetarian and other meat options are also now widely available but the real deal is rinderrouladen (beef rouladen), a popular dish in western Germany and the Rhine region.

This is a staple of family dinners and special occasions. They are usually served with potato dumplings, mashed potatoes and pickled red cabbage. A red wine gravy is an absolute requirement to round off the dish.

Sauerbraten is regarded as one Germany’s national dishes and there are several regional variations in Franconia, Thuringia, Rhineland, Saarland, Silesia and Swabia.

This pot roast takes quite a while to prepare, but the results, often served as Sunday family dinner, are truly worth the work. Sauerbraten (literally “sour roast”) is traditionally prepared with horse meat, but these days beef and venison are increasingly used.

Before cooking, the meat is marinated for several days in a mixture of red wine vinegar, herbs and spices. Drowned in a dark gravy made with beetroot sugar sauce and rye bread to balance the sour taste of the vinegar, sauerbraten is then traditionally served with red cabbage, potato dumplings or boiled potatoes.

This is another messy and not necessarily optically appealing dish, but nevertheless definitely worth trying. Himmel und erde, or himmel un ääd in Cologne (both mean “Heaven and Earth”) is popular in the Rhineland, Westphalia and Lower Saxony. The dish consists of black pudding, fried onions and mashed potatoes with apple sauce.

It has been around since the 18th century, and these days is a beloved staple of the many Kölsch breweries and beer halls in Cologne, where it goes perfectly well with a glass or three of the popular beer.

Germany’s most beautiful places

Zwiebelkuchen and federweisser

October is the month to taste the first wines of the year in Germany, and a well-known culinary treat in the south is federweisser und zwiebelkuchen (partially fermented young white wine and onion tart).

Federweisser literally means “feather white” and is made by adding yeast to grapes, allowing fermentation to proceed rapidly. Once the alcohol level reaches 4%, federweisser is sold. It is mostly enjoyed near where it is produced. Because of the fast fermentation, it needs to be consumed within a couple days of being bottled. In addition, the high levels of carbonation means that it cannot be bottled and transported in airtight containers.

In most towns and cities along the Mosel River, people flock to marketplaces and wine gardens in early October to sip a glass of federweisser and feast crispy, freshly made onion tarts called zwiebelkuchen. Because of its light and sweet taste, it pairs well with the savory, warm onion cake.

World politics in a pig’s stomach. Saumagen was made famous by former Chancellor of Germany Helmut Kohl, who (like the dish) hailed from the western Palatinate region. Kohl loved saumagen and served it to visiting dignitaries including 1980s British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and US Presidents Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton.

The literal translation of this dish is “sow’s stomach,” but saumagen is a lot less curious than its name implies.

Somewhat resembling Scottish haggis, it is prepared by using the stomach of a pig (or an artificial one) as a casing for the stuffing made from pork, potatoes, carrots, onions, marjoram, nutmeg and white pepper.

It is then sliced and pan-fried or roasted in the oven, and, as Kohl knew, goes down perfectly well with sauerkraut, mashed potatoes and a dry white wine from the Palatinate.

Pinkel mit grünkohl, or cooked kale and sausage, is a delicious winter comfort food eaten mainly in northwest Germany, especially the region around Oldenburg, Bremen and Osnabrück as well as East Frisia and Friesland.

The cooked kale is mixed with mustard and bacon, and the “pinkel” sausage (named after the pinky) is made of bacon, groats of oats or barley, beef suet, pig lard, onions, and salt and pepper.

Germans sometimes celebrate winter with a traditional so-called “Grünkohlfahrt,” where family and friends go on a brisk hike accompanied by schnapps and finished off with a warm kale dinner in a country inn.

Germans are mad about white asparagus. As soon as harvest time arrives around mid-April, asparagus dishes appear on the menus of restaurants all over Germany, from Flensburg to Munich and Aachen to Frankfurt.

This is spargelzeit, the time of the asparagus, and it is celebrated with passion. During spargelzeit, the average German eats asparagus at least once a day. This adds up to a national total of over 70,000 tons of asparagus consumed per year.

No one can truly say where this fixation with white asparagus comes from, but the first document that mentions the cultivation of this vegetable around the city of Stuttgart dates to the 1686. There are spargel festivals, a spargel route in Baden-Württemberg and countless stalls along the roads of Germany selling the “white gold.”

In restaurants, asparagus is boiled or steamed and served with hollandaise sauce, melted butter or olive oil. It comes wrapped in bacon or heaped upon schnitzel; as asparagus soup, fried asparagus, pancakes with herbs and asparagus, asparagus with scrambled eggs or asparagus with young potatoes. There is an audible sigh all over Germany when spargelzeit ends on June 24, St. John the Baptist Day.

Fried potato pancakes are so popular in Germany that we have more than 40 names for them. They are known as reibekuchen, kartoffelpuffer, reibeplätzchen, reiberdatschi, grumbeerpannekuche and so on and so on.

Another quintessential German comfort and street food, reibekuchen are often served with apple sauce, on black pumpernickel rye bread or with treacle (a type of syrup).

They’re popular all year around: in Cologne and the Rhineland they are beloved of revelers during the Karneval festivities in spring, and all German Christmas markets have reibekuchen vendors where hundreds of litres of potato dough are being processed every day during the holiday season.

Why Germany is the bread capital of the world

Rollmöpse (plural) are cooked or fried and then pickled herring fillets, rolled around a savory filling like a pickled gherkin or green olive with pimento, and have been served on the coasts since medieval times.

Becoming popular during the early 19th century when the long-range train network allowed pickled food to be transported, Rollmöpse have been a staple snack on German tables ever since.

Rollmöpse are usually bought ready-to-eat in jars and are eaten straight, without unrolling, or on bread and sometimes with labskaus (see above). And like labskaus, they are commonly served as part of the German katerfrühstück or hangover breakfast.

Germany has a vast variety of cakes, but among the most popular is the Schwarzwälder kirschtorte or Black Forest gateau.

The cake is not named after the Black Forest mountain range in southwestern Germany, but the specialty liquor of that region, Schwarzwälder kirsch, distilled from tart cherries.

Allegedly created by Josef Keller in 1915 at Café Agner in Bonn in the Rhineland, it typically consists of several layers of chocolate sponge cake sandwiched with whipped cream and sour cherries, and then drizzled with kirschwasser. It is decorated with additional whipped cream, maraschino cherries and chocolate shavings.

Its popularity in Germany grew quickly and steadily after World War II, and it’s during this period that the kirschtorte starts appearing in other countries too, particularly on the British Isles.

Whatever the reason for its success, it is both perfect for kaffee und kuchen in a German cafe on a Sunday afternoon as well as dessert.

There are rarely any strawberries in German cheesecake (or any other fruits for that matter), and the base is surely not made from crackers but freshly made dough (or even without base, like in the East Prussian version).

The filling is made with low-fat quark instead of cream cheese and egg foam is added to give it more fluff, plus lemon and vanilla for some extra freshness.

Maybe this purity and the focus on a handful of ingredients is why a version of cheesecake exits in almost every region of Germany: there’s käsekuchen, quarkkuchen, matzkuchen and even topfenkuchen in Austria.

Wherever you try it, you can be sure that it is the perfect treat with some added fresh cream and a hot cup of coffee.

This dessert is another immigrant legacy and is popular with German children.

Spaghettieis is an ice cream dish made to look like a plate of spaghetti. Vanilla ice cream is pressed through a modified noodle press or potato ricer, giving it the appearance of spaghetti. It is then placed over whipped cream and topped with strawberry sauce representing the tomato sauce and white chocolate shavings for the Parmesan.

Besides the usual dish with strawberry sauce, there are also variations with dark chocolate ice cream and nuts available, resembling spaghetti carbonara instead of spaghetti bolognese.

Spaghetti ice cream was invented in 1969 by Dario Fontanella, son of an ice cream-making Italian immigrant in Mannheim, Germany. Thankfully for us and perhaps unfortunately for Dario, he didn’t patent his spaghetti ice cream and it is today available at almost every ice cream parlor anywhere in Germany.

Dario did, however, receive the “Bloomaulorden,” a medal bestowed by the city of Mannheim, for his culinary services in 2014.